There’s more than one way to read a book

What your English teachers got wrong

There’s no way the author wrote a rainy scene to foreshadow the protagonist’s tragic ending, right…?

Right?

Don’t get me wrong, English was my favourite subject in high school and set me on the path to pretty much dedicating my life to the field. However, now that I have a couple years of university-level English under my belt, there’s something about the way we’re taught to study literature at school that doesn’t sit right with me.

But three things before getting into that:

- I’ve been out of high school for more years than I want to count so I’d like to think the approach to studying literature in school has evolved since then.

- Only so much can be taught in a high school English classroom. The literacy skills expected of teenagers are, of course, vastly different from those of young scholars in university.

- And most importantly: I’m not a teacher, just a bibliophile with a dream for the world to see what I see in stories.

The biggest issue for me when looking back to my high school English classes is that there always seemed to be just one way of reading a story and of unpacking its meaning. And I think it’s this that makes people susceptible to not taking English seriously as a subject. Because how can you possibly know why the author chose for it to rain at that particular moment in the book?

And the thing is you can’t know.

You can’t know the author’s intentions unless you’re lucky enough (as we often are these days) to engage with said author and hear their take on the work. But even then, what an author says can’t be taken as the gospel truth. Sometimes an author’s intention doesn’t translate to the story’s execution and that’s okay. The point is that we have to allow ourselves, as readers, the space to come to our own conclusions even if that means challenging the authors themselves.

In my experience, the high school English classroom didn’t really give us that space.

If the exam memo said the curtains were black to foreshadow the character’s death, then that’s why the curtains were black. And what taking English at university taught me is that the point of studying literature isn’t to find answers; it’s to raise questions.

In my first university poetry lecture, the professor told us that she didn’t want to hear anything about metaphors or similes in our analyses because that’s not what poetry’s about. In my opinion, those figures of speech are good entry points to understanding a piece of literature but they’re restrictive and reduce the work to an algebraic equation:

Black = death

Rain = sad

But reading shouldn’t be about surface-level analyses of metaphors and symbols. Instead, literature is about plunging into the uncertainties and challenges of a story to encourage conversations about human nature and our relation to the world.

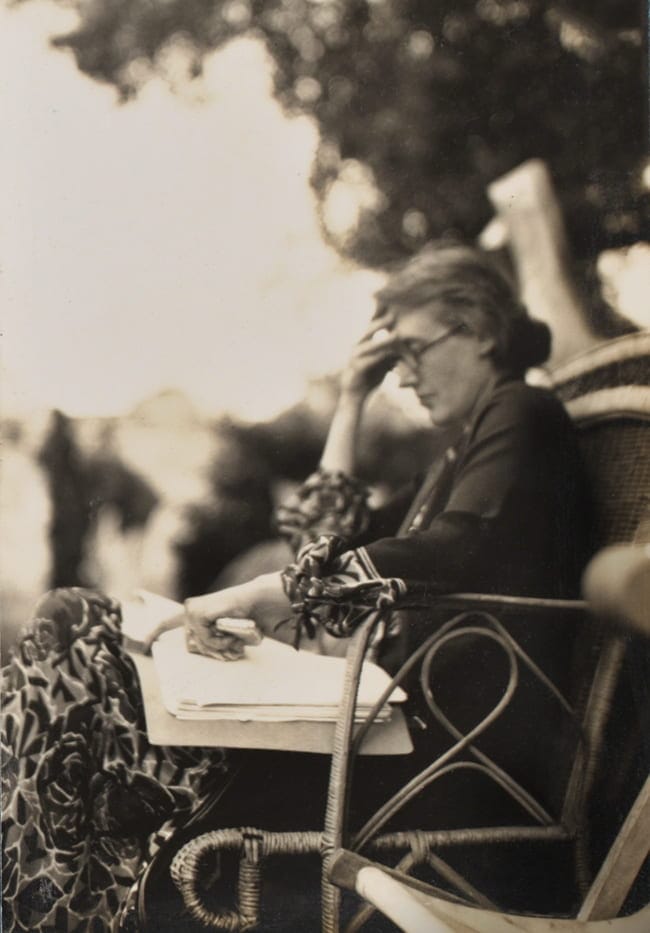

To end off, I’ll leave you with a quote from my favourite author from her essay “How Should One Read a Book?”:

Now, one may well ask oneself, strolling into such a room as this, how am I to read these books? What is the right way to set about it? There are so many and so various … One may think about reading as much as one chooses, but no one is going to lay down the laws about it. Here in this room, if nowhere else, we breathe the air of freedom.” — Virginia Woolf

If you’re finding any value, joy, or comfort from The Kulturalist, consider supporting my work at the button below. Every contribution helps to keep the words coming. Thank you for being here!