Should we still study classics?

What the real problem is

Anyone who’s studied English in some capacity knows their Austen from their Brontë and their Dickens from their Hardy. But these days it’s difficult to keep these names in the English syllabus without facing the question: why are we still studying these so-called classic authors?

Or, more specifically, why are we still studying these white — often male — authors from the west?

Although it’s necessary to question the significance of classics, it assumes two things. The first is that classics by white western authors only tell us about white western issues. And the second is that classics are synonymous with white western stories.

I consider myself lucky to have done my undergraduate in South Africa where it’s tough to ignore conversations around power and its connection with gender, race, and class. Learning in that kind of space emphasised how entangled the world’s stories are.

For example, we can’t talk about nineteenth-century British literature without talking about imperialism. As I mentioned in last week’s edition, literature doesn’t exist in a vacuum. When we read Jane Eyre, are we reading about a chaotic and fairly problematic romance? Yes. But we’re also reading about Britain’s imperial power and the marginalisation of enslaved characters if we read close enough.

By excluding novels like this from our studies, we exclude the possibility to confront and challenge western attitudes towards the rest of the world. That’s not to say, however, that we shouldn’t be re-evaluating the dominance of these classics.

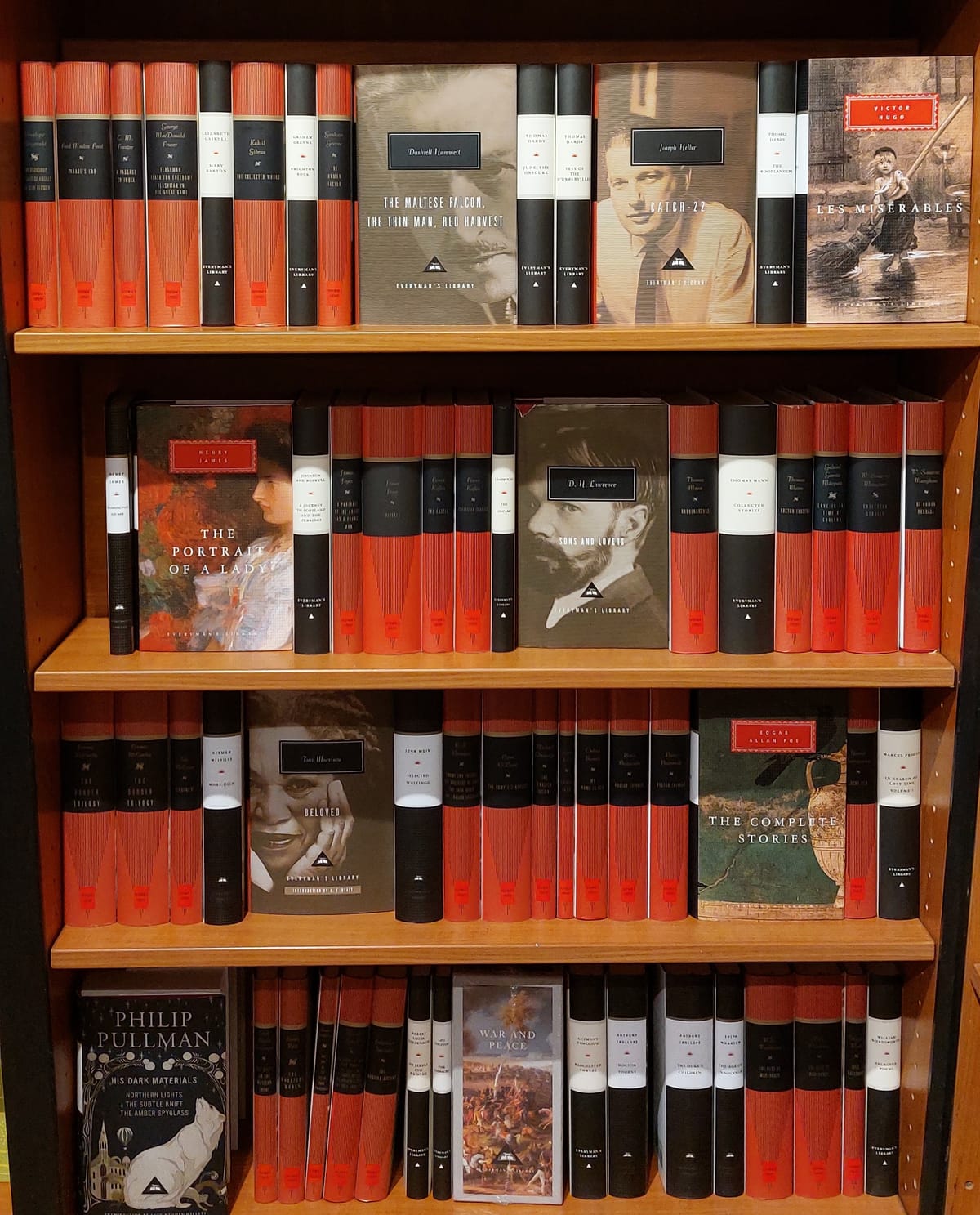

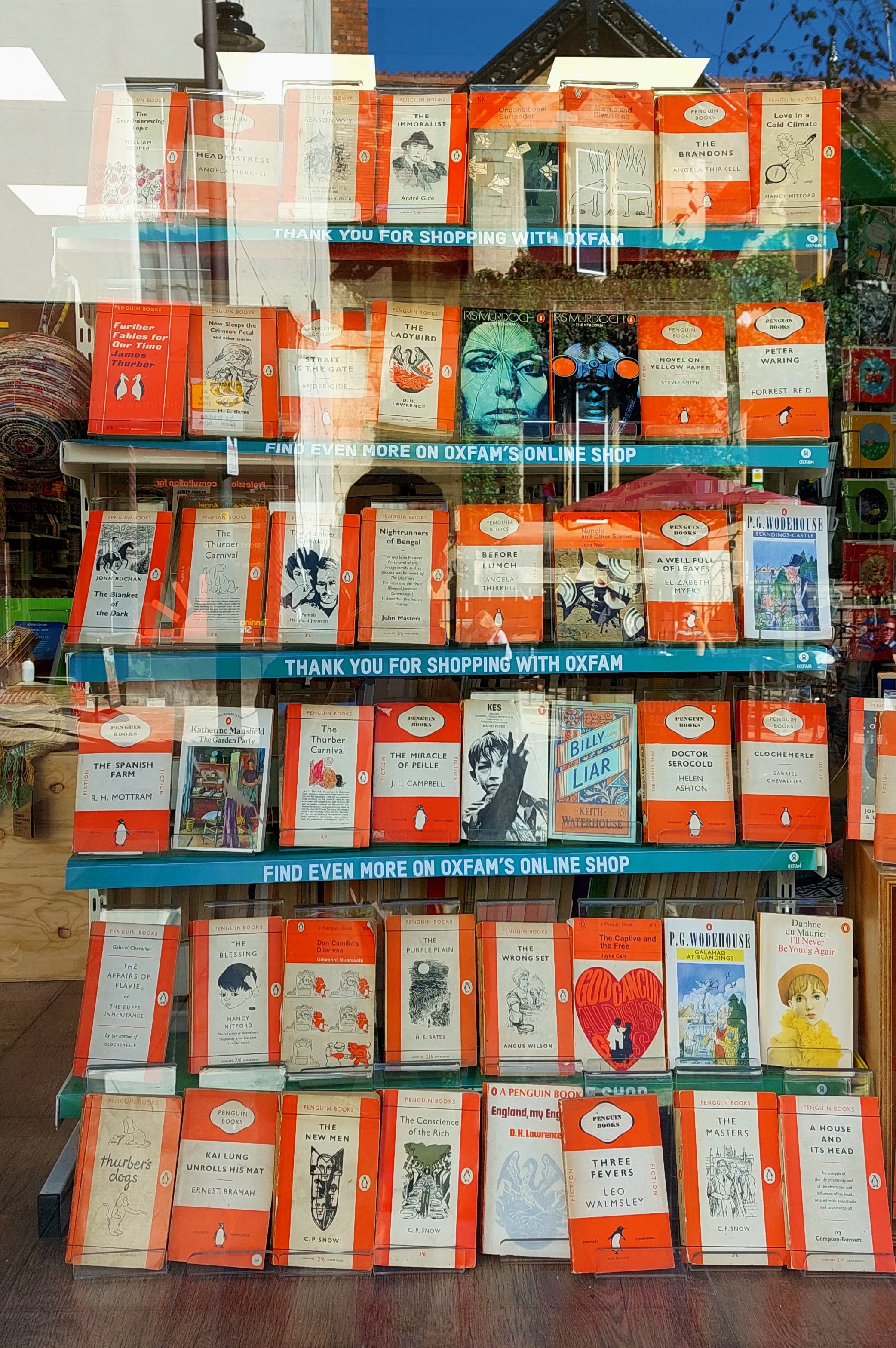

In my mind, the real problem isn’t that we’re still studying classics. The problem is that classics are often conflated with western books written by white (male) authors. And you don’t have to do much digging to find evidence of this all over the bookish side of the internet.

It’s rare to find readers of classic literature on bookstagram, booktok, or booktube who read beyond Europe and North America. But there are some creators (see: books by leynes and The Artisan Geek) who crush it when it comes to celebrating classics from outside the west.

So the issue of studying classics isn’t whether we should still study them or not. The issue we need to tackle is how we define a “classic” and how it’s decided who and who isn’t allowed into this category.

Everyone perceives classics in different ways but nonetheless, it’s harmful to perpetuate the idea that only white western stories are significant enough to be deemed classics.

Often we find classics from outside the western literary canon designated into “World Literature”, which has its pros and cons. But I do think it’s important to recognise works like Achebe’s Things Fall Apart as a classic that is just as much a part of the broader literary canon as works from white English writers for instance. Even though there’s value in calling Achebe’s work an African classic, solely categorising it in this way marks western classics as the standard and anything else as non-standard, as other.

So either we begin dismantling the commonly accepted idea of classics and the literary canon in general or we begin labelling western classics by similar criteria: Jane Eyre as a British classic or The Great Gatsby as a North American classic.

Studying classics — whether that’s classic literature, film, or art — is a fundamental part of understanding contemporary culture. But we should be active in questioning the processes determining what makes a classic a classic.

The canon isn’t some untouchable pedestal of artistic creations. It’s a flexible collection of work that should be continuously revised to reflect our society’s progression.

If you’ve found value, joy, or comfort in The Kulturalist, consider clicking the button below to support my work. Your generosity keeps the words flowing. Thank you for being here!