On the mourning of an artist

A literary pilgrimage to Virginia Woolf's house

It’s strange to mourn the loss of a life you never knew. It’s stranger yet to mourn a life that ended long before yours began. But this is often how it goes when you grow to love someone through their words written years, decades, or even centuries ago.

Falling in love with a writer is like getting to know a long-distance friend. A stranger on the other side of the world, sending letters written for you alone. Through their words, their existence is made tangible. You know they are somewhere out there, breathing their thoughts onto pages you now hold.

It’s the 30th of June, 9:22 am. I’m getting ready for my trip to Monk’s House — Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s East Sussex cottage. I button up my dress, reach into its pockets, and pull out a pair of broken earrings. I forgot those were in there. Then, a wave of thoughts crashes over me: pockets, stones, water, drowning. The realisation of her absence strikes me like a sudden death.

I’ve been reading Virginia Woolf since I was eighteen and all this time I’ve known she’s no longer here. I’ve known that her words sitting on my shelves are no more than remnants of her existence and yet, I’ve still somehow felt that she was out there somewhere: reading, roaming, writing. I now go into the day with a newfound sense of loss, knowing that her last word has been written and that I’ll have to face reading it one day.

I arrive at Southease train station at 12:07 pm and am instantly sucked into the largeness of its landscape. I walk along a wide dirt road between the farm fields and come across a bridge. “Weak bridge”, it says, “dead slow”. I stop for a moment to ground myself against the wind and look across the steady flowing water beneath it: the River Ouse. The waters that saw Virginia’s last steps and breath.

From Southease, it’s a thirty-minute walk to Rodmell village. The Woolfs’ cottage sits at the top of The Street (yes, that is the name of their road). Its whitewashed walls make it unassuming from the outside compared to its neighbours. Their single garage, no bigger than a small living room, serves as the visitor centre. From this space alone, it’s clear that this experience is not one of grandeur typical of other major heritage sites. This is a place of quietness, where greatness can be found in smallness.

The ground floor of the house is open to the public, which includes the conservatory/greenhouse, living room, dining room, kitchen, and Virginia’s bedroom. Upstairs is onsite accommodation for National Trust staff as well as Leonard Woolf’s room and library, which has a balcony that can be glimpsed from the garden. Because of concerns about structural integrity and space, the Woolfs’ upstairs rooms are not accessible. But it’s difficult to be disappointed when there’s so much to get lost in throughout the rest of the property.

“[Monk’s House] will be our address for ever and ever. Indeed, I’ve already marked out our graves in the yard which joins our meadow.”

— Virginia Woolf

Walking through Monk’s House, I feel like more of a guest than a fleeting tourist. Apart from the dining room, there’s freedom to wander around the rooms where there are no physical boundaries between visitors and the history held in the furniture, books, and artworks. When moving around the house, volunteers not only share in-depth knowledge of the rooms and lives that inhabited them but they also share a hushed warning, “Please mind your head!”, when approaching the cottage’s stooping doorways.

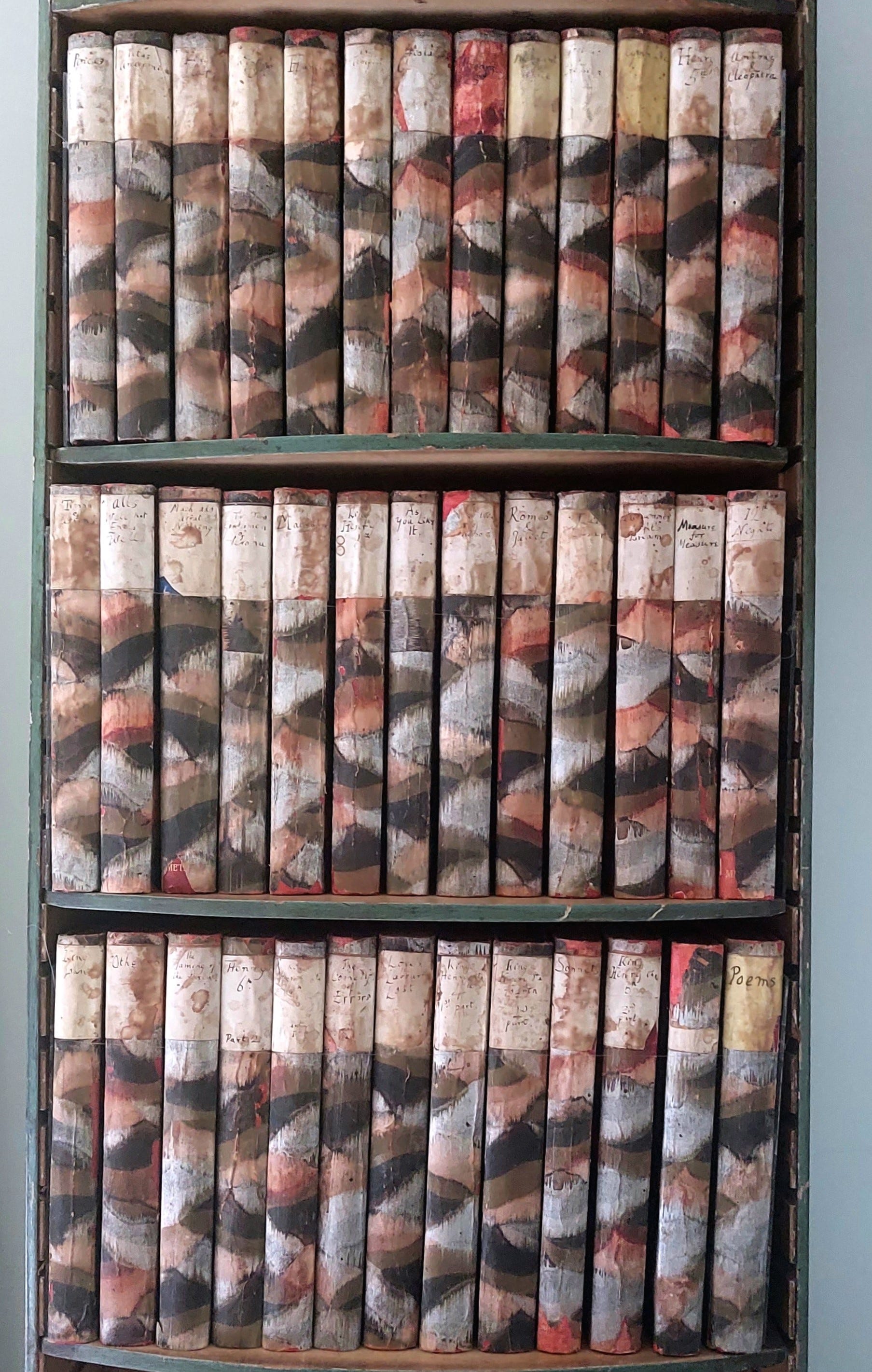

In Virginia’s bedroom (initially built to be a writing room before deciding she didn’t like writing there) the bed is framed by a wall of books. Besides her bed is a fireplace decorated with ceramic tiles designed by sister Vanessa Bell. The central mosaic shows a lighthouse, reminiscent of their childhood holidays in St Ives, Cornwall. And on a corner floor tile is the inscription: “VB to VW 1930”. Most memorable, however, is Virginia’s personal collection of Shakespeare’s works with each copy individually covered by her and housed in what’s presumed to be a specially built floating shelf. Upon a closer look, at the top of each spine is the work’s title in her handwriting.

While the house itself is modest, the garden stretches out endlessly. It is simultaneously wild and landscaped. Sculptured busts of Leonard and Virginia sit atop a stone wall, marking the burial sites of their ashes. Guests allow each other the space to have a moment alone near Virginia and I am somewhat relieved to see that I’m not the only one holding back tears beneath the tree shading her face.

Virginia’s writing room — a converted garden shed towards the back of the property — is divided into two separate spaces. On the one side is an open area with informational displays about Monk’s House and its various distinguished guests from the Bloomsbury Group. On the other side, shielded by a museum-like glass window, is Virginia’s writing desk. The partition created by the glass exemplifies the sacredness of the space that was the birthplace of her most renowned works.

It’s now 2:06 pm. I’m writing this on the bench overlooking a pond and Virginia’s sculpture. Monk’s House, its garden and rooms, is so alive with her that the re-remembering of her death hits again and again as if for the first time.

The wind is thrashing my hair into tangles around my face. I consider wishing for it to be a perfect summer day with cloud-speckled blue skies and a breeze whispering between leaves. But no day can be anything more than what it’s meant to be.

I can’t bring myself to leave. But we must go on and on and on.

“I know that V. will not come across the garden from the Lodge, and yet I look in that direction for her. I know that she is drowned and yet I listen for her to come in at the door. I know that this is the last page and yet I turn it over.”

— Leonard Woolf

Thank you for spending this time with me for this super special post.

If you’ve found value, joy, or comfort in The Kulturalist, consider clicking the button below to support my work. Your generosity keeps the words flowing.

If you enjoyed reading it, you might like this one too: