How to say the last goodbye

Even small feelings are big in Àma Gloria (2023)

Knowing which moment will be the last we get to spend with someone we love is rare.

Our lives are punctuated with small goodbyes, big goodbyes, and small goodbyes that should’ve been bigger had only we realised sooner. Yet in the film Àma Gloria, the predestined separation of the two main characters looms over the story as we are taken along on the pair’s last summer together.

Cléo is a six-year-old living in France who can’t imagine life without her nanny, Gloria. Whether it’s learning to roll her “R’s” or softly blowing on her wounded hands after a fall on the playground, Cléo’s childhood experiences are grounded in the presence of Gloria by her side. “It’s weird to me,” Cléo whispers to Gloria who’s sharing recollections of her past, “because I only have memories of you.”

But in the space of a phone call, everything changes between Cléo and Gloria.

When we’re small, everything about life feels all-consuming, especially when it seems like our bodies are too small to contain a feeling we’ve never felt before. Àma Gloria’s writer and director, Marie Amachoukeli, captures this through the camera’s closeness to its protagonists.

When we first meet Cléo and Gloria, their worlds revolve around each other. Their faces fill up entire frames so the adoration they have for each other glowing in their eyes is tangible through the screen. But when Gloria has to return to her home in Cape Verde and Cléo spends the summer with her there, suddenly Cléo has to share the screen with the many other people in Gloria’s life. The little girl’s enraged prayer demanding to have Gloria to herself makes palpable her jealousy and her struggle to sit within this new emotion.

The movie’s focus on Cléo’s grappling with the fact she’s but one piece of Gloria’s life could come across as a sense of entitlement Cléo has for her nanny’s affection. This could even go so far as to be interpreted as a reflection of colonial dynamics in which a European — though be it a six-year-old girl in this case — takes an African person as their possession and refutes any attempt made towards gaining independence. While this postcolonial element is certainly bubbling beneath the surface, Cléo and Gloria’s relationship is, as Jessica Kiang writes, too multi-layered to be simplified into a single allegory.

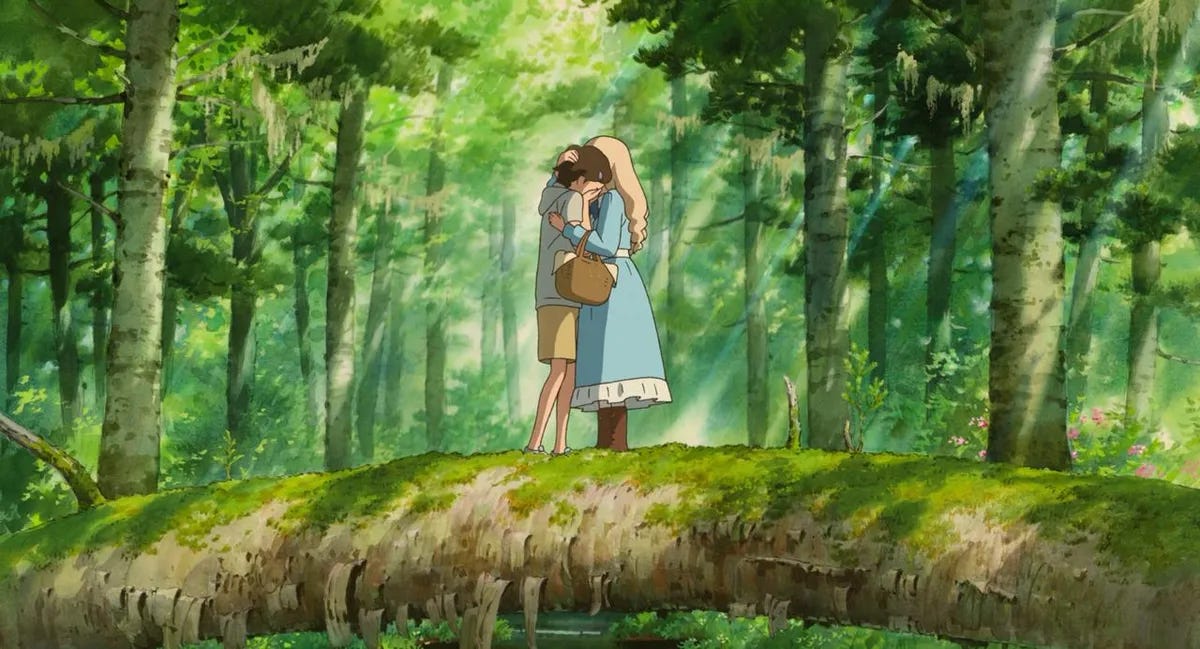

In Àma Gloria, we see Cléo confronted by the reality that no matter how deeply she feels the warmth of Gloria’s love, she is but one planet orbiting her nanny’s sun. During one of the hand-painted animated scenes scattered throughout the film, a child is embraced in the arms of a woman. The two figures spin around until the colours of their clothing and bodies are swept up into each other, becoming a palette of indistinguishable shapes. But when the time comes for Cléo to return to France, there’s an unspoken acknowledgement that they have to finally detach from one another.

As Cléo walks away from Gloria, she steps into a reality in which she must create a world for herself beyond Gloria. Yet, with Gloria’s necklace hanging around her neck, the film becomes a reassurance that we can never really depart from someone without carrying a piece of their love with us wherever we go next.

Àma Gloria expresses the abrupt awakening we have as children — and even as adults — when we discover we can’t be someone’s entire world although that person might be everything to us. But as the story progresses, Cléo begins to understand that Gloria’s love for her doesn’t diminish despite having to share it.

Because no matter how many times we hand over our hearts to the people we love and no matter how many more people we come to love during our lives, we’ll never reach the limit of how much our hearts are capable of holding.

If you’re finding any value, joy, or comfort from The Kulturalist, consider supporting my work at the button below. Every contribution helps to keep the words coming. Thank you for being here!

If you enjoyed reading this, you might also like this post about the histories and memories we inherit in our childhoods: